Cerdanyola del Vallès, 31st March 2020 Scientists have made a breakthrough in the development of a new generation of electronics that will require less power and generate less heat. It involves exploiting the complex quantum properties of electrons - in this case, the spin state of electrons.

In a world first, the researchers - led by a team of physicists from the University of Leeds - have announced in the journal Science Advances that they have created a 'spin capacitor' that is able to generate and hold the spin state of electrons for a number of hours. Previous attempts have only ever held the spin state for a fraction of a second.

In electronics, a capacitor holds energy in the form of electric charge. A spin capacitor is a variation on that idea: instead of holding just charge, it also stores the spin state of a group of electrons - in effect it 'freezes' the spin position of each of the electrons.

That ability to capture the spin state opens up the possibility that new devices could be developed that store information so efficiently that storage devices could get very small. A spin capacitor measuring just one square inch could store 100 Terabytes of data.

Dr Oscar Cespedes, Associate Professor in the School of Physics and Astronomy who supervised the research, says: "this is a small but significant breakthrough in what could become a revolution in electronics driven by exploitation of the principles of quantum technology“.

"At the moment, up to 70 per cent of the energy used in an electronic device such as a computer or mobile phone is lost as heat, and that is the energy that comes from electrons moving through the device's circuitry. It results in huge inefficiencies and limits the capabilities and sustainability of current technologies. The carbon footprint of the internet is already similar to that of air travel and increases year on year.“ he adds. "With quantum effects that use light and eco-friendly elements, there could be no heat loss. It means the performance of current technologies can continue to develop in a more efficient and sustainable way that requires much less power."

Dr Matthew Rogers, one of the lead authors, also from Leeds, comments: "our research shows that the devices of the future may not have to rely on magnetic hard disks; instead, they will have spin capacitors that are operated by light, which would make them very fast, or by an electrical field, which would make them extremely energy efficient.

"This is an exciting breakthrough. The application of quantum physics to electronics will result in new and novel devices."

Some of the world's most advanced experimental facilities were used as part of the investigation. The researchers have carried out experiments at the BOREAS beamline of ALBA. Synchrotron light allows to visualise the atomic structure of matter and to investigate its properties. Low energy muon spin spectroscopy at the Paul Scherrer Insitute in Switzerland was used to monitor local spin changes under light and electrical irradiation within billionths of a meter inside the sample. A muon is a sub-atomic particle. The results of the experimental analysis were interpreted with the assistance of computer scientists at the UK's Science and Technical Facilities Council, home to one of the UK's most powerful supercomputers.

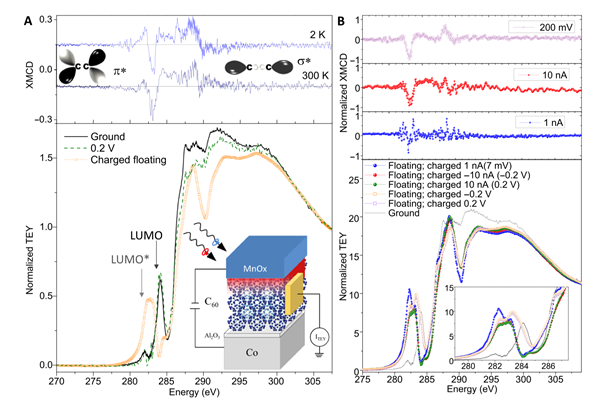

Fig.1 Spin-polarized charge trapping. (A) Bottom: NEXAFS at the carbon K-edge in a SiO2//Co(30)/Al2O3(1.6)/ C60(15)/MnOx(2.5) junction—film thickness in brackets in nanometers. After a bias is applied and then removed, the LUMO broadens and shifts to 283 eV. This persists until the electrodes are connected to a common ground. Top: p* LUMO states extend up to ~290 eV. In this region, XMCD measurements in the charged state after a bias show spin polarization at room and low temperature. (B) Changes in the carbon K-edge (bottom) and XMCD (top) with the applied voltage or current. XMCD is measured in the floating charged state. The different impedance of the source meter leads to changes in the trapped charge during the measurement and in the LUMO* peak. The higher internal impedance of the voltage source results in better signal-to-noise XMCD measurements. (Image and figure caption taken from the Science Advances publication).

How a spin capacitor works

In conventional computing, information is coded and stored as a series of bits: e.g. zeroes and ones on a hard disk. Those zeroes and ones can be represented or stored on the hard disc by changes in the polarity of tiny magnetized regions on the disc. With quantum technology, spin capacitors could write and read information coded into the spin state of electrons by using light or electric fields.

The research team were able to develop the spin capacitor by using an advanced materials interface made of a form of carbon called buckminsterfullerene (buckyballs), manganese oxide and a cobalt magnetic electrode. The interface between the nanocarbon and the oxide is able to trap the spin state of electrons. The time it takes for the spin state to decay has been extended by using the interaction between the carbon atoms in the buckyballs and the metal oxide in the presence of a magnetic electrode.

The scientists believe the advances they have made can be built on, most notably towards devices that are able to hold spin state for longer periods of time.

Reference: T. Moorsom, M. Rogers, I. Scivetti, S. Bandaru, G. Teobaldi, M. Valvidares, M. Flokstra, S. Lee, R. Stewart, T. Prokscha, P. Gargiani, N. Alosaimi, G. Stefanou, M. Ali, F. Al Ma'Mari, G. Burnell, B. J. Hickey, O. Cespedes. Reversible spin storage in metal oxide--fullerene heterojunctions. Science Advances, 20 March 2020: EAAX108